Quantum Mordançage: When Chemistry Meets Coherence

Sometimes you have to break things to see what's underneath. In quantum computing, we spend all our time trying to maintain coherence—keeping qubits isolated, stable, controlled. But what if instead of preserving that delicate quantum state, you deliberately disrupted it? What if the disruption itself could reveal something about quantum behavior that our instruments miss?

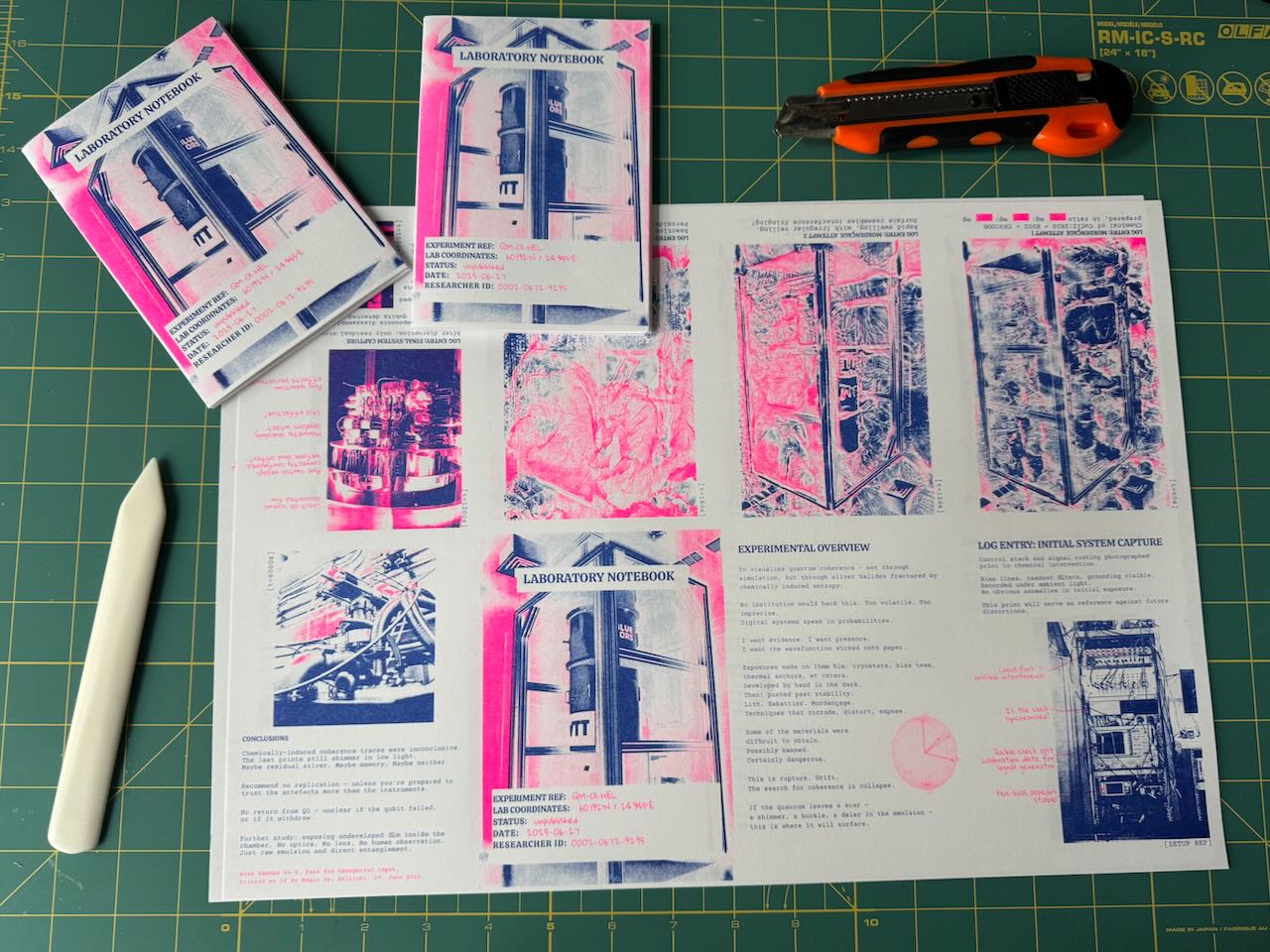

That's the premise behind my latest project: photographing quantum computing hardware, then attacking those photographs with mordançage until the emulsion buckles and lifts, searching for traces of quantum coherence in the chemical chaos.

The mad scientist proposition

Here's the hypothesis: quantum systems leave signatures we can't directly observe. Our measurement tools collapse wavefunctions by definition. But silver halide emulsions—those ancient light-recording crystals—might capture something in between. Not the measurement, but the presence. The shimmer. The uncertainty itself.

I photographed the prototypes of superconducting quantum computers. Not glamour shots—technical documentation. Cryostats. Bias tees. Thermal anchors. Control stacks. The physical infrastructure that maintains quantum coherence at millikelvin temperatures. Shot on 35mm film, developed normally, printed in the darkroom, then pushed into chemically-induced entropy.

Mordançage as methodology

For those unfamiliar: mordançage is a darkroom process that physically lifts the emulsion from its paper base - see my previous post explaining the process

Why mordançage specifically? Because it mirrors quantum decoherence. A stable system (the photograph) subjected to environmental disruption (the chemistry) undergoes irreversible change. The original information is still there, but transformed, distorted, partially lost. Like a quantum state collapsing, but frozen mid-process.

The prints themselves

I used multiple alternative processes on the quantum computer photographs:

- Mordançage: Some prints went through the full copper chloride treatment, emulsion lifting and buckling around the quantum hardware - these form the core of the work

- Lith printing: Others were lith-developed for that distinctive grain and tonal separation, without the physical disruption

- Sabattier effect: The cover image used this partial reversal technique—re-exposing during development to create those characteristic Mackie lines and tonal inversions

Each process brought something different. The mordançage created physical dimension—buckles and veils. The lith prints gave infectious development patterns that spread like uncertainty through the image. The Sabattier reversal on the cover suggested states flipping, superposition collapsing.

The time-based series shows the same image at different stages of chemical intervention: 60 seconds, 120 seconds, 180 seconds, suggesting the quantum decay emerging and escalating with time (of course, this to be compared with the real qubit decay times in the order of microseconds)

From darkroom to Risograph

The original mordançage prints are unique objects—you can't reproduce that specific buckling, that exact crystallization pattern. But I wanted to share the work, make it distributable. Enter Risograph printing.

I scanned the mordançage prints and separated them into two plates:

- Cool Plate: Medium Blue: the stable, the mechanical, the classical infrastructure, the formal documentation

- Warm Plate: Fluorescent Pink: the disruption, the quantum, the uncertainty, the handwritten notes

The colour choice wasn't arbitrary. Blue reads as technical, solid, trustworthy. Fluorescent pink is unstable—it shifts under different light, never quite settling into one hue. The overlap creates purples that shouldn't exist, much like quantum superposition.

The Riso's registration drift adds another layer of uncertainty. Each print varies by 1-2mm, and each zine is hand-folded, making every copy unique. The mechanical imprecision echoes the fundamental uncertainty of quantum measurement.

The zine as quantum object

The final form: an zine using “magic” folding— folded and cut to create a 8-page zine from a single A3 sheet.

Inside: the time-series progression of mordançage destroying/revealing the quantum hardware. Lab notebook aesthetics—typewriter fonts, hand annotations, timestamps. The kind of documentation you'd find if someone was actually trying to photograph quantum states and slowly going mad from the impossibility.

Printed at If By Magic in Helsinki, June 2025. Edition of 15. Each one different due to Riso variance. Some copies have more pink. Others more blue. The ones where registration was way off might be the most accurate—maximum uncertainty principle.

First showing: Experimental 2025

I brought the zines to Experimental 2025 in Barcelona this July—a gathering of people working at the intersection of art and emerging technologies. It was the first time I'd shown or sold the work publicly, and I think it was a moderate success, despite the somewhat niche concept.

What this actually is

Let me be clear: this is not science. I'm not claiming to have photographed quantum states or that mordançage reveals hidden quantum signatures. That would be absurd.

But it is an investigation. Using the language and materials of one discipline (alternative photographic processes) to think about problems in another (quantum computing). The mordançage process, with its chemical violence and unpredictable results, becomes a metaphor for quantum measurement. The degrading emulsion mirrors decoherence. The Risograph's mechanical uncertainty echoes Heisenberg's principle.

It's about making the invisible visible, even if what becomes visible is just our own attempt to see. The failure to capture quantum states becomes, through creative failure, its own kind of success.

Why this matters

We live in an age of precise digital reproduction. Quantum computers promise even more precision—calculations impossible with classical systems. But quantum mechanics itself is fundamentally about uncertainty, probability, superposition.

Using deliberately unstable processes—mordançage, Risograph—to document quantum computing hardware isn't contradiction. It's alignment. The medium matches the subject: both deal with states that can't be pinned down, outcomes that vary with observation, information that exists in multiple forms simultaneously.

Plus, there's something satisfying about using 19th-century chemistry to document 21st-century physics. As if all technology is ultimately about the same thing: trying to see what can't quite be seen.

With thanks to V. Furs for thoughtful input on layouting and printmaking, and for not laughing when I explained the project. Printed at If By Magic, Helsinki, June 2025. First shown at Experimental 2025, Barcelona, July 2025.

References and further madness

- Mordançage technique: Christina Anderson's “The Experimental Darkroom”

- Quantum Computing in Finland

- If By Magic: Riso studio based in Helsinki

- Experimental Photo Festival: Where photographic art meets alternative processes, annually in Barcelona