Chromoskedasic Sabattier: Colour from Silver, Light from Scattering

Part 1 of 3 in the Chromoskedasic Sabattier series | Next: Part 2 →

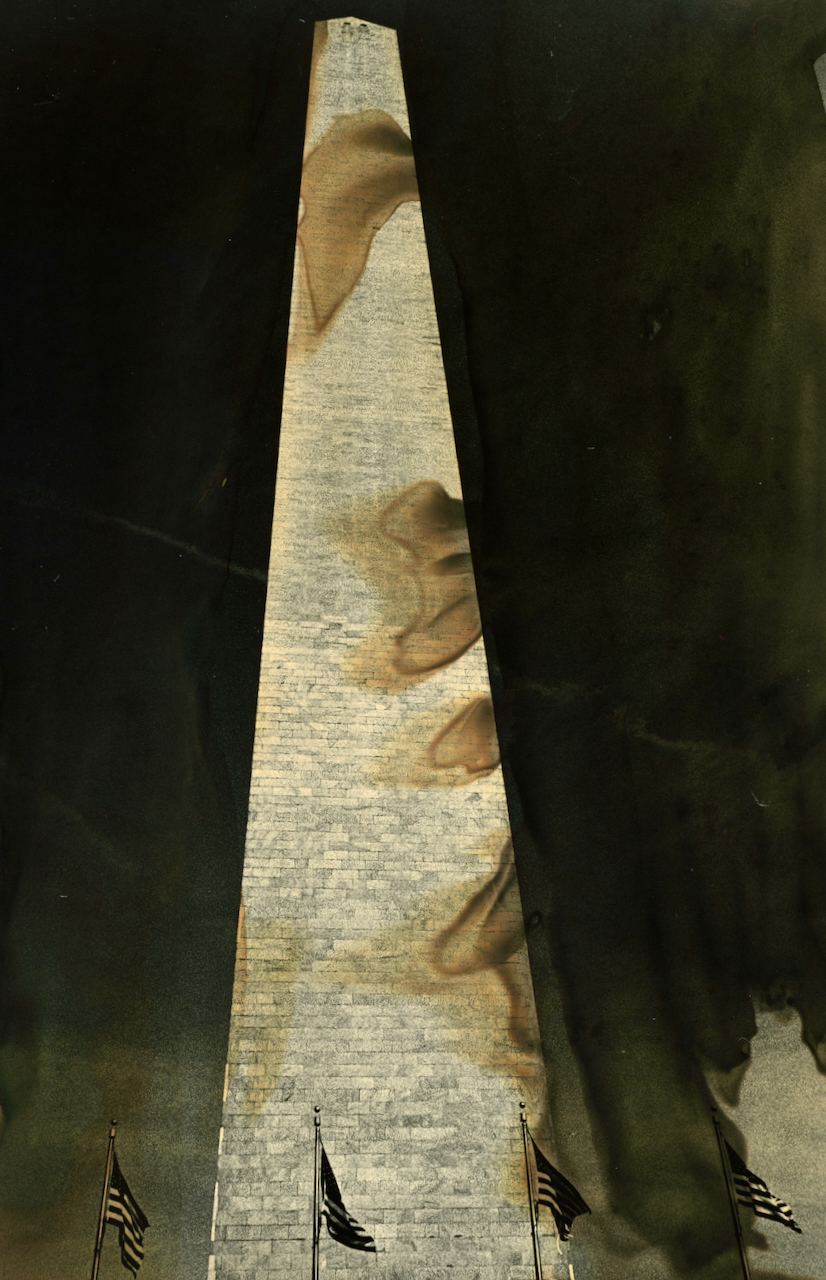

The print came out of the activator tray warm amber where it had been grey seconds before. Not stained amber, not toned amber—the silver itself had transformed, scattering light at wavelengths it had no business scattering. I tilted the wet paper and watched the colour shift, iridescent, metallic, impossible from materials that contained nothing but silver and gelatin.

This is chromoskedasic Sabattier printing: a technique that creates colour from black and white materials through physics rather than chemistry. Unlike toning, where chemical compounds replace or coat the silver, chromoskedasic printing manipulates silver particle sizes until they scatter specific wavelengths of light. The phenomenon is called surface plasmon resonance, and it's the same physics that makes colloidal gold appear ruby red and gives stained glass windows their glow. Centuries-old art, cutting-edge nanoscience, and darkroom practice converging in a tray of alkaline solution.

I first encountered chromoskedasic prints in Christina Z. Anderson's work—warm bronze tones emerging from standard Ilford paper, colours that seemed to require dyes or pigments but contained neither. The prints had a metallic quality that shifted with viewing angle, almost holographic. For someone who spends their professional life thinking about quantum phenomena in superconducting systems, the underlying physics was irresistible. Here was a darkroom technique grounded in the same plasmonic effects I encounter in nanophotonics literature.

This post begins a three-part series exploring chromoskedasic Sabattier printing. Here I'll cover history and context—what the process is, how it was discovered, and how it relates to the Sabattier and mordançage techniques I've written about elsewhere. The second post examines the physics and chemistry in depth: Mie scattering, surface plasmon resonance, and the counterintuitive chemical sequence that enables colour formation. The third documents my experiments applying the technique to photographs of Washington DC's Metro system and monuments.

What Is Chromoskedasic Printing?

The name derives from Greek: chroma (colour) and skedasmos (scattering or dispersion). The term describes the physical mechanism directly—colour arising from the scattering of light by particles, not from selective absorption by dyes or pigments.

This distinction matters. In conventional colour photography—whether chromogenic prints, inkjet outputs, or oil paintings—colour arises through subtractive mixing. Dyes absorb specific wavelengths while transmitting others. Cyan dye absorbs red light; magenta absorbs green; yellow absorbs blue. The colour we perceive is what remains after absorption.

Chromoskedasic prints operate through an entirely different mechanism. The silver particles in the emulsion don't absorb light selectively—they scatter it. When particles reach specific sizes (roughly 10-100 nanometers), they scatter certain wavelengths more efficiently than others due to resonance effects. The scattered light creates the appearance of colour, while transmitted light shows complementary colours.

This is structural colour—colour arising from physical structure rather than chemical pigmentation. It's how peacock feathers achieve their iridescence without containing blue or green pigments, how morpho butterfly wings shimmer, how soap bubbles produce rainbow patterns from materials that are themselves colourless. The colour comes from the interaction between light waves and physical structures at scales comparable to visible wavelengths.

The practical result is prints with qualities impossible through conventional means: metallic sheens, colours that shift with viewing angle, warm amber and bronze tones emerging from paper containing nothing but silver and gelatin. The effect is genuinely unique—neither toned nor dyed nor painted, but structurally coloured through the physics of nanoscale light-matter interaction.

A Process Born from Accident

Like many photographic discoveries, chromoskedasic printing emerged from a mistake that someone was curious enough to investigate rather than discard.

The story begins at the University of California, San Francisco in 1980. Dr. Dominic Man-Kit Lam, a scientist working on visual perception and photoreceptor biochemistry, was exploring the optical properties of silver halide systems. During experiments with partially processed photographic materials, he observed something unexpected: colours appearing on paper that should have remained purely monochrome.

Rather than dismissing this as contamination or error, Lam investigated systematically. What conditions produced colour? What variables controlled the hue? What was the mechanism? Over the following years, working largely in isolation, he developed the technique into a reproducible process—though one he used primarily for his own artistic work rather than publishing detailed methodology.

The scientific explanation came from an unexpected source. In 1989, Bryant W. Rossiter, a research chemist at Eastman Kodak's Research Laboratories in Rochester, New York, encountered Lam's work and recognised the underlying physics. Rossiter understood that the colours weren't chemical in origin—they arose from Mie scattering by colloidal silver particles suspended in the gelatin matrix. He had the physical chemistry background to explain why specific particle sizes produced specific colours, and the connection to broader work on colloidal metal optics.

Lam and Rossiter collaborated to document the phenomenon, resulting in their landmark 1991 article in Scientific American: “Chromoskedasic Painting.” That paper established both the theoretical foundation and practical methodology. The colours arise from localized surface plasmon resonance in silver nanoparticles—collective oscillations of conduction electrons that resonate with incident light at wavelengths determined by particle size and shape. Particles around 20-40 nm produce yellows; 40-60 nm yields amber and orange; 60-100 nm creates bronze, brown, and russet tones.

The name “chromoskedasic” was coined by Lam and Rossiter to describe this mechanism precisely. Unlike “solarisation” (which technically refers to extreme overexposure reversal effects, often confused with Sabattier) or “Sabattier effect” (which describes tone reversal from mid-development fogging), “chromoskedasic” names the physical phenomenon: colour from scattering.

The Lineage: From Rochester to Bozeman

Scientific discoveries require champions to survive. Without practitioners willing to teach, refine, and document a technique, even elegant processes disappear. Chromoskedasic printing nearly suffered this fate.

Following the 1991 Scientific American article, interest briefly flared. Kodak, recognising commercial potential, developed the Ektamatic S-10 Stabilizer and A-10 Activator—chemistry specifically optimised for chromoskedasic work. Articles appeared in photography magazines. Workshops were offered. Then the analogue world contracted as digital imaging accelerated, and the technique faded into obscurity.

Dr. William L. Jolly kept the flame alive through the 1990s and early 2000s. Emeritus Professor of Chemistry at UC Berkeley, Jolly combined deep scientific understanding with serious photographic practice. He had published extensively on inorganic chemistry (his textbook Modern Inorganic Chemistry went through multiple editions) and understood the electron transfer reactions underlying the process. His 1997 book Solarization Demystified: Historical, Artistic and Technical Aspects of the Sabatier Effect devoted substantial chapters to chromoskedasic processing, including reformulated chemistry as the original Kodak products became scarce. Jolly continued experimenting and teaching until his death in 2014.

Christina Z. Anderson, Professor of Photography at Montana State University, became the technique's most important contemporary advocate. Anderson studied alternative processes extensively, including direct instruction from Jolly, and has spent decades documenting and teaching historical and experimental techniques. Her books—Gum Printing and Other Amazing Contact Printing Processes (2017), Cyanotype: The Blueprint in Contemporary Practice (2019), and most comprehensively The Experimental Darkroom (2022)—provide accessible instruction for processes otherwise poorly documented. For chromoskedasic printing specifically, she worked with Freestyle Photographic Supplies and master printer Alan Bean to develop modern chemical formulations after Kodak discontinued the Ektamatic products.

Today, a small but dedicated community practices chromoskedasic printing. Artists including Bridget Conn (who teaches workshops and has developed excellent instructional materials), Jan Cook, Jessica Hays, Frank Lopez, Sara Silks, and Ralph Whitehead have developed distinctive approaches. The process appears occasionally in alternative photography workshops and publications. But it remains genuinely obscure—far less known than cyanotype, platinum printing, gum bichromate, or even mordançage.

Relationship to Other Experimental Techniques

Understanding where chromoskedasic printing fits among experimental darkroom processes helps clarify what makes it distinctive.

Standard Sabattier effect: I've written elsewhere about the Sabattier effect—the technique where a print receives secondary light exposure partway through development, causing partial tone reversal and the distinctive Mackie lines at density boundaries. The effect was first documented in the 1850s (by H. de la Blanchère, among others) and named after Armand Sabatier, who described it in 1862. Chromoskedasic Sabattier incorporates this mid-process light exposure but adds chemical intervention that produces colour rather than simple tone reversal. The “Sabattier” in the name indicates that room-light exposure during processing is essential to colour formation—the light creates new latent image centres that participate in the colour-forming reactions.

Mordançage: My mordançage work uses copper chloride, hydrogen peroxide, and glacial acetic acid to attack the developed silver image, weakening the gelatin matrix and allowing emulsion to lift and be physically manipulated. The chemistry is aggressive, and the process creates physical texture—veils of lifted emulsion, exposed paper base, three-dimensional sculptural effects. Chromoskedasic printing is gentler and aims for different results. It manipulates the state and size of silver particles to produce optical effects while leaving the print surface essentially intact. Where mordançage transforms photographs toward sculpture, chromoskedasic transforms them toward painting.

Toning: Traditional toners—selenium, sepia, gold, iron blue—chemically convert silver particles or deposit other metals onto them. In selenium toning, for example, selenium replaces some of the silver, shifting colour toward purple-brown. In gold toning, gold deposits onto silver particles, shifting toward blue-black. The particle size remains similar; the chemistry changes. Chromoskedasic printing works through the opposite mechanism: the chemistry (silver in gelatin) remains fundamentally the same, but particle size changes. This is why chromoskedasic results look so different from toned prints—the colour mechanism is entirely distinct.

Chemigrams: Pierre Cordier's chemigram process (developed from 1956 onward) applies developer, fixer, and other chemicals to photographic paper without camera exposure, creating abstract images through direct chemical interaction under room light. Chromoskedasic printing shares the concept of manipulating chemistry outside conventional processing sequences but works with camera-exposed images rather than purely abstract chemical marks.

The closest historical relatives might be the interference-based colour processes of the late 19th century—Gabriel Lippmann's Nobel Prize-winning interference photography (1891-1908), which created colour through standing wave patterns in thick emulsions. These processes were abandoned as technically impractical for commercial use, but they operated on similar principles: engineering the physical structure of silver to interact with light in wavelength-selective ways, producing colour without dyes.

Why Washington DC?

For my chromoskedasic experiments, I chose photographs from Washington DC—specifically the Metro system and the monuments. The choice wasn't arbitrary.

The DC Metro stations, designed by architect Harry Weese and opened beginning in 1976, represent some of the most striking brutalist architecture in American public transit. The system's visual signature—coffered concrete vaults that expand toward the platforms, dramatic escalators tunneling through indirect lighting, the interplay of geometric structure and controlled illumination—creates images with strong compositional bones and clear tonal separation.

These characteristics make Metro photographs particularly suited to chromoskedasic treatment. The process works by transforming highlight areas while leaving shadows largely unchanged; images with clear separation between light and dark show effects most dramatically. The repeating geometric elements—coffered ceiling panels, escalator handrails, platform edge markers—provide visual structure that survives significant transformation. Even when colours shift unexpectedly or develop unevenly, the underlying architecture holds the image together.

There's also conceptual resonance. Washington is a city built on transformation—political will converted into physical monument, abstract democratic ideals made concrete (literally) in marble and granite. Chromoskedasic printing performs its own transformation, taking the silver-and-gelatin of black and white photography and revealing unexpected colour through physical restructuring. Both involve making materials speak in new ways through precise intervention.

The Metro system adds another layer. These are spaces of transit, of movement, of people flowing through engineered environments. The chromoskedasic process involves its own flows—chemistry moving across the print surface, silver particles nucleating and growing, colour emerging through controlled chemical instability. The frozen moments captured on film become unfrozen in the darkroom, transformed by reactions that refuse to stabilise until arrested.

What Makes This Process Difficult

Chromoskedasic printing is genuinely challenging. Unlike many alternative processes where experience leads to predictable results, this technique involves so many interacting variables that complete control remains elusive even for experienced practitioners.

The primary difficulty is timing. The chemical sequence—stabilizer, then activator, with light exposure at specific stages—must occur within narrow windows. Insufficient stabilizer time and the subsequent chemistry fails to produce colour. Excessive stabilizer time overshoots into different, often unwanted effects. Temperature affects reaction rates. Solution age and exhaustion change behaviour. Even paper batch variations shift results.

Then there's the interaction with image content. Different tonal regions respond differently. Shadow areas with dense, fully-developed silver remain largely unchanged—the particles are too large and too interconnected for the chemistry to restructure. Highlight areas with sparse silver distribution transform dramatically. Mid-tones fall somewhere between, their response depending on precise local conditions. Learning to predict how a given negative will transform requires many attempts.

The colour palette, while beautiful, is constrained compared to other processes. Warm tones dominate: yellows, ambers, bronzes, golds, occasional blue-violets at the edges. The full spectrum available through conventional toning or chromogenic processes isn't accessible. Physics constrains what's possible—silver nanoparticles only scatter certain wavelength ranges efficiently.

Finally, exact reproducibility is essentially impossible. You can develop consistent approaches that produce similar results, but precise reproduction of a specific print requires controlling variables that resist control. Each piece emerges from a unique confluence of chemistry, timing, temperature, and intervention. Some practitioners embrace this as integral to the medium's character; others find it frustrating.

Preview: What Comes Next

In the second post of this series, I examine the physics and chemistry in detail. We'll explore Mie scattering theory, surface plasmon resonance, and why silver nanoparticles produce specific colours at specific sizes. I'll provide chemical formulations for stabilizer and activator, explain why the counterintuitive application sequence matters, and discuss how variables including pH, temperature, and paper choice affect results. For those with physics or chemistry background, I'll connect the phenomenon to broader contexts in nanophotonics and colloidal science.

The third post documents my practical experience with the DC photographs. I'll describe my specific workflow—which involves partial development in the darkroom followed by chromoskedasic treatment outdoors under natural light—discuss successes and failures, and offer observations that might help others attempting the technique.

What I hope to convey across this series is both technical depth and aesthetic potential. Chromoskedasic printing is grounded in serious physics — yet it produces results that feel almost alchemical: colour emerging from colourless materials, light itself becoming the pigment.

The experimental darkroom has always been where science meets art, where understanding chemistry and physics enables creative possibilities unavailable through intuition alone. Chromoskedasic Sabattier printing represents one of the most elegant examples of this intersection: a technique requiring knowledge of optics, electrochemistry, and colloid science, yet producing results that transcend technical explanation. The prints aren't illustrations of physics—they're physics made visible, light scattering rendered permanent in silver and gelatin.

References

Primary Sources

Lam, Dominic Man-Kit, and Bryant W. Rossiter. “Chromoskedasic Painting.” Scientific American 265, no. 5 (November 1991): 80-85. [The foundational paper introducing the technique and explaining the physical mechanism. Available on JSTOR.]

Jolly, William L. Solarization Demystified: Historical, Artistic and Technical Aspects of the Sabatier Effect. Buffalo, NY: William L. Jolly, 1997. [Comprehensive treatment including extensive chromoskedasic chapters with reformulated chemistry.]

Books

Anderson, Christina Z. The Experimental Darkroom: Contemporary Uses of Traditional Black & White Photographic Processes. New York: Routledge, 2022. [Chapter 4 covers chromoskedasic printing with contemporary formulations and practical instruction.]

Anderson, Christina Z. Experimental Photography Workbook. Self-published, earlier editions. [Predecessor to The Experimental Darkroom with chromoskedasic coverage.]

Li, Vanessa Lok-wa, and Bryant W. Rossiter. The Art and Artistry of Dominic Man-Kit Lam: Volume 1, Chromoskedasic Painting. Singapore: World Scientific, 2017. [Monograph on Lam's artistic work with extensive reproductions.]

Articles

Anderson, Christina Z. “Quick and Easy Chromoskedasic Sabatier.” Photo Techniques (May/June 2010). [Practical introduction available through Freestyle Photographic Supplies website.]

Anderson, Christina Z. “Chromoskedasic Printing Revisited.” Photo Techniques (May/June 2010). [Updated techniques and formulations.]

Bean, Alan. “The Black and White Corner: Chromoskedasic Painting.” View Camera (September/October 1992): 40-43. [Early practical guide.]

Online Resources

Freestyle Photographic Supplies. “Quick and Easy Chromoskedasic Sabatier.” https://www.freestylephoto.biz/chromoskedasic-sabatier [Christina Z. Anderson's practical guide.]

AlternativePhotography.com. “Chromoskedasic Sabattier: A Step-by-Step Guide.” https://www.alternativephotography.com/chromoskedasic-sabattier-a-step-by-step-guide/ [Process walkthrough with images.]

Related Scientific Literature

Mie, Gustav. “Beiträge zur Optik trüber Medien, speziell kolloidaler Metallösungen.” Annalen der Physik 330, no. 3 (1908): 377-445. [Original theoretical treatment of light scattering by spherical particles.]

Paramelle, David, et al. “A Rapid Method to Estimate the Concentration of Citrate Capped Silver Nanoparticles from UV-visible Light Spectra.” Analyst 139 (2014): 4855-4861. [Modern treatment of silver nanoparticle optical properties.]

Kelly, K. Lance, et al. “The Optical Properties of Metal Nanoparticles: The Influence of Size, Shape, and Dielectric Environment.” Journal of Physical Chemistry B 107, no. 3 (2003): 668-677. [Comprehensive review of plasmonic nanoparticle optics.]

Historical Context

Crawford, William. The Keepers of Light: A History and Working Guide to Early Photographic Processes. Dobbs Ferry, NY: Morgan & Morgan, 1979. [Historical context for experimental photographic techniques.]

James, Christopher. The Book of Alternative Photographic Processes. 3rd ed. Boston: Cengage Learning, 2015. [Comprehensive alternative process reference.]