Breaking RA4 Apart: When Mordançage Meets Colour Layers

The conventional wisdom is clear: mordançage doesn't work on colour materials. No silver, no reaction. Case closed. The chemistry textbooks are unequivocal—RA4 colour paper creates images through cyan, magenta, and yellow dyes, not metallic silver. After the bleach step strips away the developed silver, you're left with pure chromogenic dyes suspended in gelatin. Nothing for copper ions to bite into.

So why are these prints lifting? Why, after a few minutes in heated mordançage solution, does the emulsion begin to bubble and separate? Why can I peel entire colour layers away from the resin-coated base like removing cling film from a window?

These questions led me into uncharted chemical territory. What started as curiosity about whether mordançage could affect colour materials has become an exploration of RA4 paper's hidden architecture—the adhesion layers, the gelatin matrices, the boundaries between cyan, magenta, and yellow that normally remain invisible until chemistry forces them apart.

The Impossible Chemistry

Let's establish what shouldn't be happening. In a standard RA4 process, the workflow runs: developer → bleach-fix (or separate bleach, then fix) → wash. The developer converts exposed silver halides to metallic silver whilst simultaneously creating colour dyes through chromogenic coupling. The bleach then oxidises that metallic silver to soluble silver salts, which the fixer removes entirely. What remains are pure dye clouds—no metallic silver in the final image.

Mordançage chemistry, as it is usually described, requires metallic silver to function. The copper(II) chloride needs something to oxidise. The reaction cascade that weakens gelatin depends on that initial electron transfer from silver to copper. Without silver, the chemistry should be inert. The solution should sit there, doing nothing.

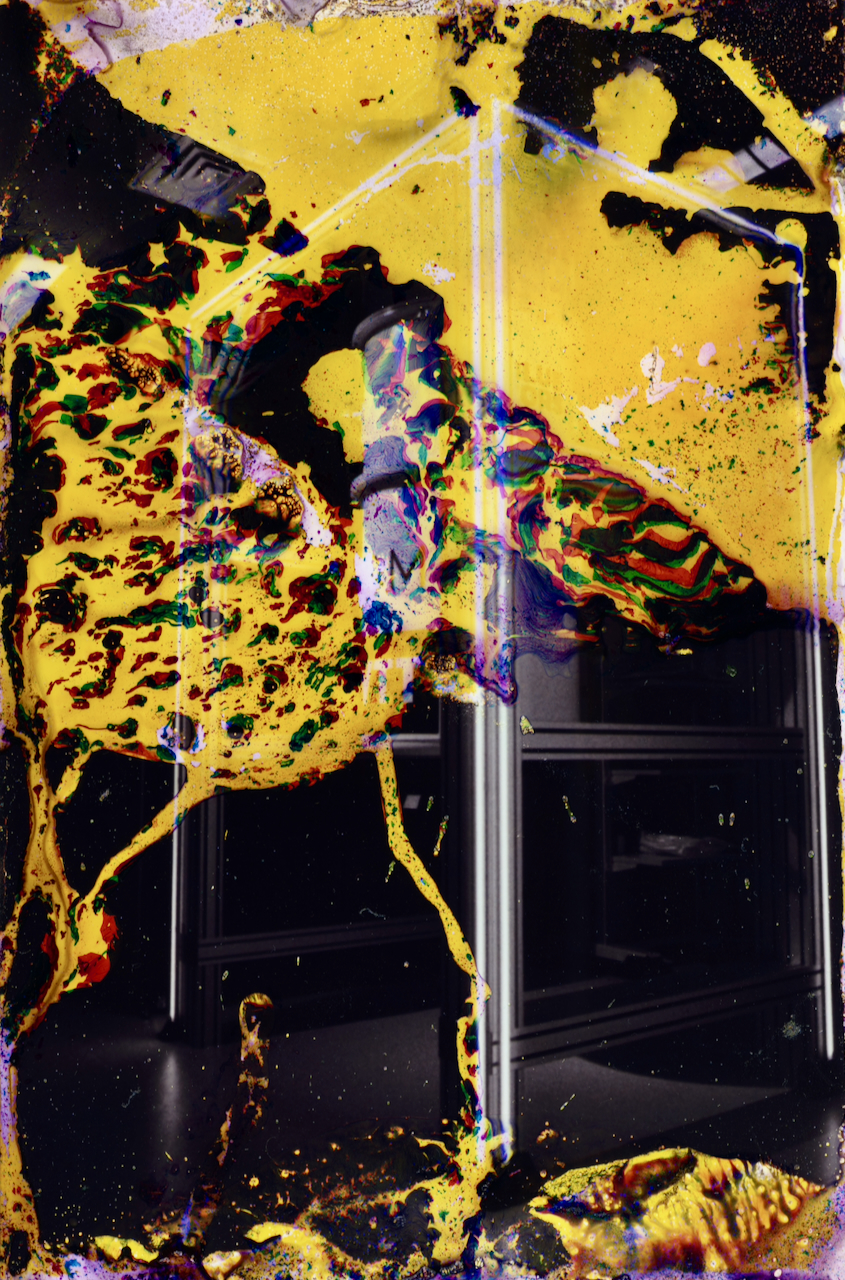

Yet here I am, watching bubbles form across the surface of a fully processed Fuji Crystal Archive print. The emulsion swells, distorts, then begins to separate from the base.

Sometimes it lifts in sheets. Sometimes in bubbles that burst to reveal the white polyethylene base beneath. Sometimes distinct colour layers separating from each other, cyan peeling away from magenta, yellow clouds floating free.

The Alternative Hypothesis: Beyond Silver Chemistry

After some experimentation, I'm working with a different theory. What if the mordançage solution isn't primarily attacking silver at all in these RA4 applications? What if we're seeing something else entirely—a direct chemical assault on the adhesion layers and gelatin structure that has nothing to do with the classical mordançage mechanism?

Consider the brutal chemistry we're deploying: concentrated hydrogen peroxide, glacial acetic acid, copper chloride, all held warm at roughly 35°C. Even without silver to oxidise, this cocktail remains seriously aggressive. The hydrogen peroxide alone, at 35% concentration, is a powerful oxidising agent that attacks organic materials. The glacial acetic acid drops the pH below 2, causing massive gelatin swelling. The warmth accelerates everything.

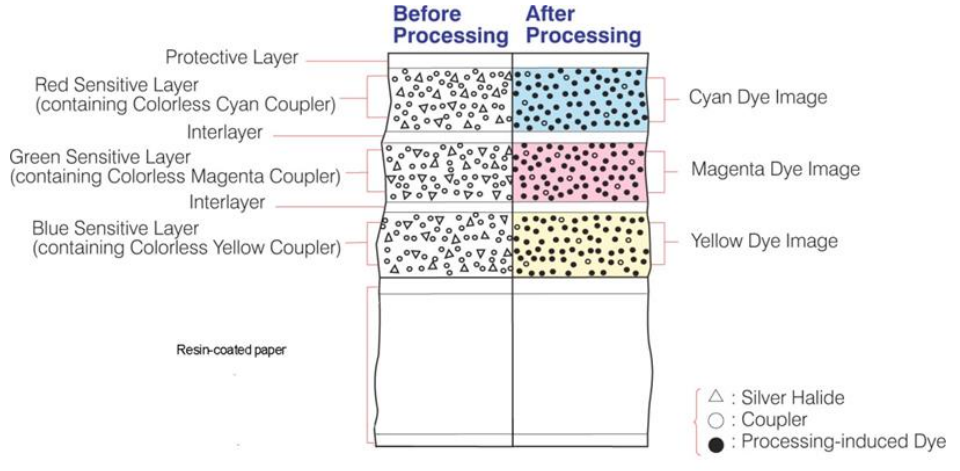

RA4 paper architecture differs fundamentally from traditional black and white papers. The emulsion isn't just gelatin with silver halides—it's a complex multilayer structure:

- Supercoat: Protective top layer

- Red-sensitive layer: Contains cyan dye couplers

- Interlayer: Prevents the diffusion of developer-derived molecules into neighbouring layers

- Green-sensitive layer: Contains magenta dye couplers

- Interlayer: Prevents the diffusion of developer-derived molecules into neighbouring layers

- Blue-sensitive layer: Contains yellow dye couplers

- Adhesion layer: Binds emulsion to resin-coated base

- Resin coating: Polyethylene layer

- Paper base: The actual paper fibre

Each boundary between these layers represents a potential failure point when subjected to extreme chemical stress.

For these experiments, I use modern RC colour paper simply because it is what remains available; fibre-based colour papers are essentially unobtainable in regular darkroom practice. That scarcity makes the peculiar vulnerability of RA4-on-RC all the more interesting.

The Heated Assault: Temperature as Catalyst

The breakthrough came with temperature. At room temperature, RA4 prints resist the mordançage solution almost completely. The emulsion might swell slightly, colours might shift, but the layers hold together. Raise the working temperature to somewhere around 35°C, and everything changes.

The warmth serves multiple functions. It accelerates chemical reactions—what might take hours at 20°C happens in minutes closer to 35°C. It increases molecular motion, allowing the aggressive chemistry to penetrate deeper into the emulsion structure. Most critically, it weakens the adhesion layers that bind everything together [web:10][file:4].

Modern RA4 papers use sophisticated adhesion promoters to lock the emulsion to the polyethylene base. These are typically titanium- or chromium-based compounds that create molecular bridges between the organic gelatin and the synthetic resin coating. They're designed to survive normal processing chemistry. They're not designed to survive concentrated hydrogen peroxide around 35°C whilst simultaneously being attacked by acid.

The Colour Layer Phenomenon

The most fascinating aspect of this process is the occasional visible separation of colour layers. In a normally processed RA4 print, the three dye layers exist as an integrated sandwich, impossible to distinguish or separate. But under extreme chemical stress, boundaries emerge.

When the emulsion lifts cleanly, I sometimes catch glimpses of pure cyan or magenta regions—evidence that the layers aren't lifting uniformly. The chemical attack seems to preferentially weaken certain interlayer boundaries. My hypothesis: each layer has slightly different gelatin formulations, different hardening levels, different chemical vulnerabilities. The mordançage solution exploits these differences.

This selective attack creates the yellow–green chromatic effects visible in prints left to dry with residual chemistry. As the trapped solution continues working between partially separated layers, it creates colour shifts that would be impossible through normal colour processing. We're seeing subtractive colour in reverse—not the removal of colour layers but their physical and chemical isolation from each other.

Mechanical intervention: Unlike traditional mordançage where the emulsion often lifts spontaneously, RA4 sometimes requires encouragement. A gentle scratch with a fingernail or brush can initiate lifting that then propagates across the print. The chemistry weakens the structure; mechanical force provides the failure point.

Timing windows: Too short, and nothing happens. Too long, and the entire emulsion dissolves into coloured soup. The sweet spot—typically around 4–7 minutes at roughly 35°C in fresh solution—yields controllable lifting with maintained colour integrity.

Safety Escalation: This Isn't Standard Mordançage

If regular mordançage demands respect, heated RA4 mordançage demands reverence. We're combining multiple hazard vectors:

Chemical hazards: 35% hydrogen peroxide causes immediate chemical burns. Glacial acetic acid vapours even around 35°C are significantly more aggressive than at room temperature. Copper compounds remain toxic. On top of this, there is the unknown element of whatever compounds are released when RA4 chemistry breaks down under these conditions.

Thermal hazards: Warmer chemistry increases vapour pressure. That means more aggressive fumes, faster evaporation, and increased respiratory risk. The warmed solution can cause thermal burns on top of chemical burns.

Unknown decomposition products: We're forcing colour chemistry into conditions it was never designed to experience. The chromogenic dyes, the colour couplers, the stabilisers—all of these might decompose into unexpected compounds. Without proper analytical work, we can't know exactly what we're creating.

Required safety protocol:

- Fume hood or exceptional ventilation (mandatory—not optional)

- Chemical splash goggles (sealed; vented lab specs are not enough)

- Thick nitrile or neoprene gloves (latex will not suffice)

- Chemical-resistant apron

- Closed-toe shoes

- Emergency shower or at least copious running water within reach

Contemporary Context: A Technique Without Precedent

Extensive research reveals no documented precedent for this specific technique. Elizabeth Opalenik, the modern master of mordançage, works exclusively with black and white materials. Christina Z. Anderson's comprehensive guides don't mention colour applications. The alternative process forums—APUG, Photrio, the various Facebook groups—contain no sustained discussions of RA4 mordançage, at least at the time of writing.

The closest parallel might be experiments in bleach-bypass C‑41 film, where retained silver enables mordançage-like effects on colour negatives. But even that works through traditional silver chemistry. What is happening here—attacking fully processed colour prints with no retained metallic silver—appears to be genuinely novel.

This isn't entirely surprising. The overlap between colour darkroom workers and alternative process practitioners has historically been small. Colour processing's complexity and temperature criticality discouraged experimentation. The materials cost more. The chemistry expires faster. Most alternative process artists gravitated towards black and white, where variables were more controllable and materials more forgiving.

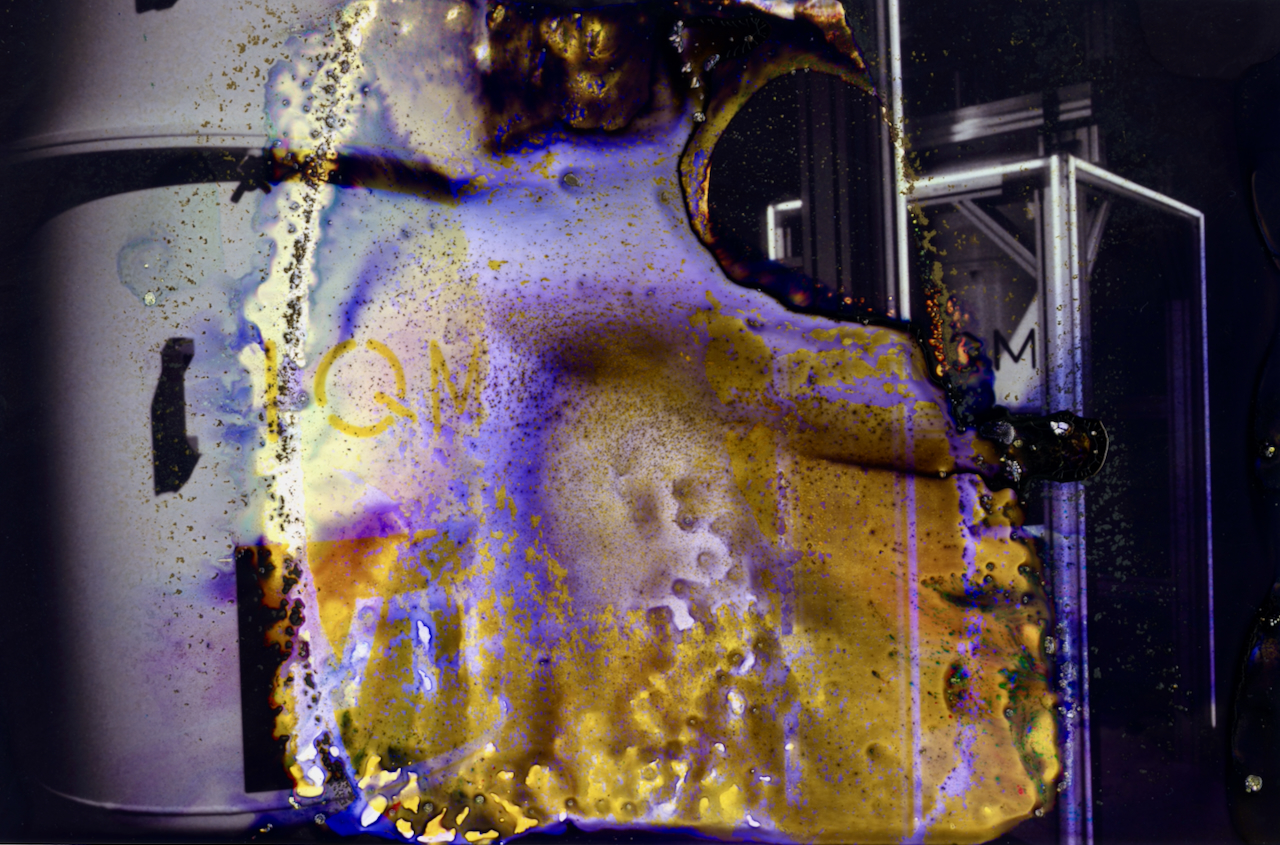

The Imperfect Archive: Trapped Chemistry as Extended Reaction

The most striking effects emerged accidentally. Prints pulled from the chemistry and left to dry without complete rinsing continued evolving for hours, even days. The residual mordançage solution, trapped between partially separated layers, kept working. The yellow–green aureoles spreading across the prints weren't stains—they were ongoing chemical reactions creating new chromogenic effects.

This presents an archival nightmare but an artistic opportunity. These prints exist in slow-motion transformation. The trapped chemistry creates effects impossible to achieve through controlled processing—colour clouds that seem to breathe, boundaries that shift depending on humidity, images that refuse to stabilise.

One could attempt to arrest these reactions through extensive washing, but something would be lost. The ongoing instability is part of the work's meaning—photographs that refuse to be fixed, colours that won't be contained, images actively decomposing and recomposing themselves.

Technical Observations and Patterns

After dozens of prints, patterns emerge:

Cyan lifts first: The top layer seems most vulnerable to separation, which fits the known RA4 layer stack with the red-sensitive/cyan-forming layer nearest the surface.

Edge effects dominate: Like traditional mordançage, dramatic effects concentrate where chemistry can penetrate from multiple angles—edges, scratches, any break in the emulsion surface.

Colour density affects lifting: Heavily exposed areas with maximum dye and gelatin density often lift earlier than highlights. Dense regions appear to provide more material for the swollen, weakened gelatin to lose its grip.

Future Investigations

This work opens numerous research directions:

Chemical analysis: Mass spectrometry or related techniques could identify what compounds form during the reaction. Are we seeing dye decomposition, altered couplers, or new chromogenic products? Understanding the chemistry could enable more precise control.

Alternative chemistry formulations: If copper chloride isn't essential in the absence of silver, what other oxidisers or catalysts might work? Could we achieve similar effects with completely different, possibly safer chemistry?

Selective layer removal: Can we develop techniques to remove specific colour layers whilst preserving others? Imagine removing only cyan to reveal the magenta–yellow image beneath.

Hybrid processes: What happens when we combine this with other alternative techniques? RA4 mordançage followed by toning? Sequential layer lifting with different chemistry between stages?

Digital hybrids: These lifted colour layers could be scanned at various stages, creating digital composites impossible through purely photographic means.

The Larger Implications

This technique challenges fundamental assumptions about photographic processes. We've been told colour and alternative processes don't mix—that chromogenic materials exist in a separate universe from historical techniques. Chemistry refuses those neat categories.

More broadly, this work suggests vast unexplored territory in experimental colour photography. Whilst the alt‑process community has exhaustively explored many historical black and white techniques, colour remains largely virgin territory for experimental manipulation. The complexity that once discouraged experimentation now offers rich possibilities for those willing to venture into unstable, unpredictable processes.

Working with RA4 mordançage means accepting imperfection, embracing accident, collaborating with chemistry that refuses complete control. The results can't be precisely repeated. Each print emerges from a unique moment of chemical chaos—temperature, timing, mechanical intervention, and pure chance combining to create something that shouldn't exist according to the textbooks.

Why This Matters Now

In an era when colour photography means primarily digital capture and inkjet output, returning to chromogenic materials with experimental intent feels almost archaeological. We're excavating the physical structure of colour photography itself—literally peeling apart the layers that create photographic colour.

This matters because it reveals colour photography as constructed rather than natural. When we can physically separate cyan from magenta, we see how arbitrary and artificial photographic colour has always been. The smooth colour gradients we accept as “realistic” are actually discontinuous layers of dye, only appearing continuous because they're normally inseparable.

The technique also speaks to contemporary concerns about permanence and degradation. Whilst traditional photography prizes archival stability, these prints celebrate their own destruction. They're photographs in active decomposition, images that refuse the stability we expect from colour prints. In a digital age of perfect preservation, there's something compelling about photographs that insist on their own material transformation.

Standing in the darkroom, watching colour layers peel apart, I'm reminded that photography's experimental future might lie not in new technologies but in misusing existing ones. Every established process contains potential for subversion. Every “impossible” reaction might just be waiting for someone willing to add heat, increase concentration, or simply refuse to accept that something can't be done.