Sabattier in the City of Lights

One of the great privileges of my work in quantum hardware is the opportunity to travel. This past year, a research trip brought me to Paris, and I brought my camera along to capture the city between conference sessions and lab visits. When I returned to the darkroom, I found myself drawn to experimenting with these Parisian images through the Sabattier effect.

The History of an Accident

The Sabattier effect has one of photography's most fitting origin stories: it was discovered repeatedly, almost always by accident. As far as I can tell, the phenomenon was first described in print by H. de la Blanchère in 1859, then again in 1860 by multiple researchers including L.M. Rutherford, C.A. Seely, and Count Schouwaloff. French zoologist Armand Sabatier published work on the process in 1860 and correctly described the phenomenon in 1862, though he couldn't explain why it occurred. His name was misspelled with a double “t” in subsequent literature, which is why we now call it the “Sabattier effect” rather than “Sabatier effect”.

Throughout the 19th century, the effect was “discovered” many times by many photographers, as it tends to occur whenever a light is switched on inadvertently in the darkroom while a film or print is being developed. The technique remained largely a curiosity until Man Ray perfected it in the 1930s, reportedly after fellow artist Lee Miller accidentally exposed his film in the darkroom (coincidentally, Lee Miller was also the inspiration for Lee Smith in the recent Civil War movie). Man Ray quickly adopted the technique as a means to “escape from banality,” transforming darkroom accidents into intentional artistic practice, and to this date, is perhaps the most famous practitioner.

The Chemistry of Reversal

Understanding what happens during Sabattier requires looking at the behavior of silver halide crystals. When photographic paper is first exposed in an enlarger, light strikes silver halide molecules, creating latent image centers—essentially activation sites that mark where silver will form during development. During normal development, these exposed centers transform into metallic silver while the developer simultaneously eliminates the centers of remaining unexposed silver halides.

The magic happens with the second exposure. When the partially developed print is flashed with light while still in the developer, the remaining unexposed silver halides—those that would normally stay clear—suddenly become exposed. These newly formed silver bodies are much larger than the silver centers formed during the first exposure, and they overpower them, causing tone reversal. Dark areas that were heavily developed remain relatively unchanged, while lighter areas that retained more unexposed silver halides undergo dramatic transformation.

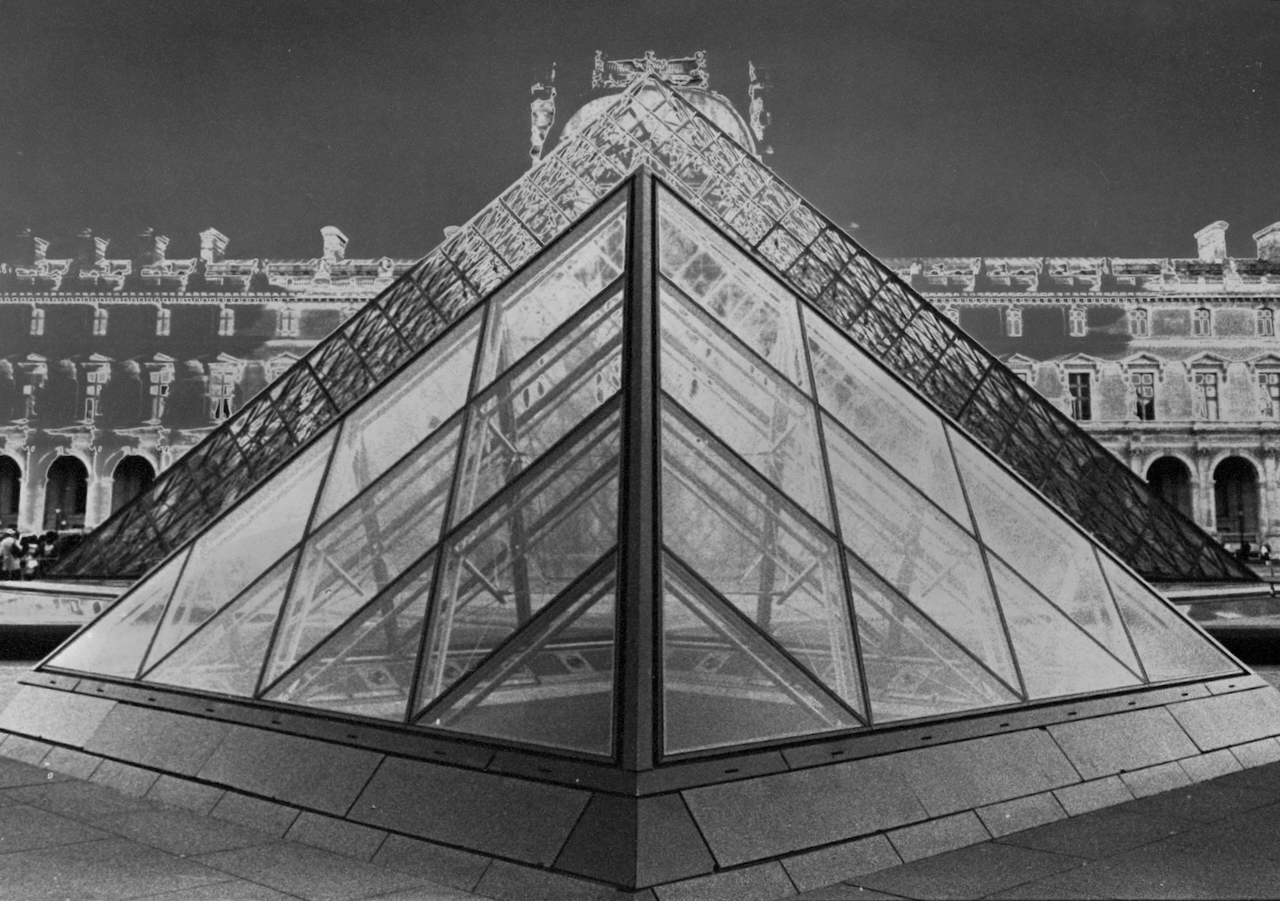

This creates the characteristic appearance of Sabattier prints: partial tone reversals, distinctive edge effects (called Mackie lines), and an eerie quality where shadows and highlights exist in uncertain relationship. The optical screening effect—where already-developed silver shields unexposed grains from the second exposure—contributes to the distinctive halos and boundaries between reversed and non-reversed areas.

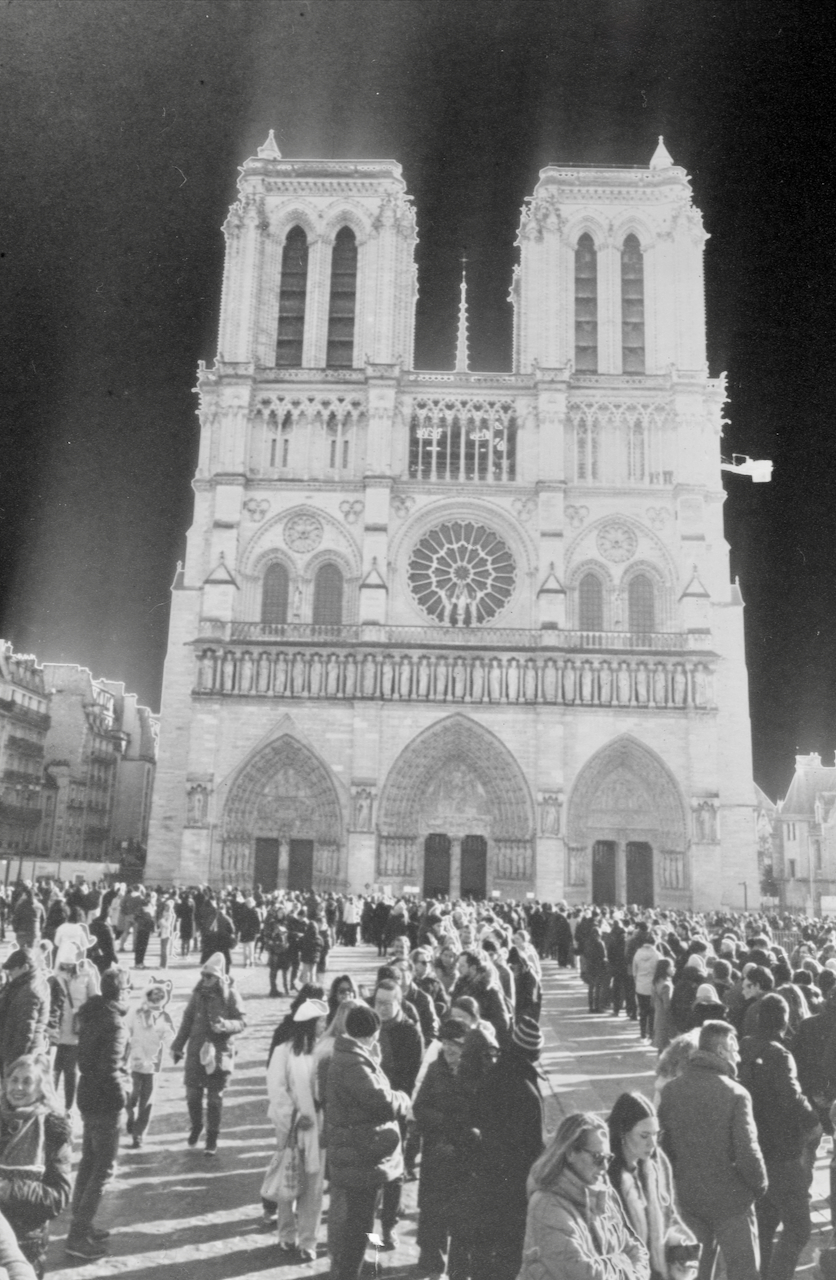

Why Sabattier for Paris

Beyond the poetic connection between Paris as the City of Lights and a technique built on light intervention, there's something conceptually appropriate about using Sabattier for this particular city. Paris isn't just luminous—it's a city of excess. Too rich in history, too dense with monuments, too saturated with cultural significance. The Sabattier process, which fundamentally involves too much light, mirrors this overwhelming quality. Just as Sabattier embraces surplus light to create new forms, working with Paris photographs through this technique allows one to engage with the city's overwhelming nature productively.

Technical Approach and Precise Control

The Sabattier process rewards experimentation, but I wanted more precision than most historical accounts describe. I developed the prints in Adox chemistry, and rather than using a simple flash or room light, I performed the second exposure using a second enlarger. This approach allowed me precise control over both the timing and aperture—essentially controlling exactly how much light was introduced during the critical moment.

From Street Photography to Chemical Intervention

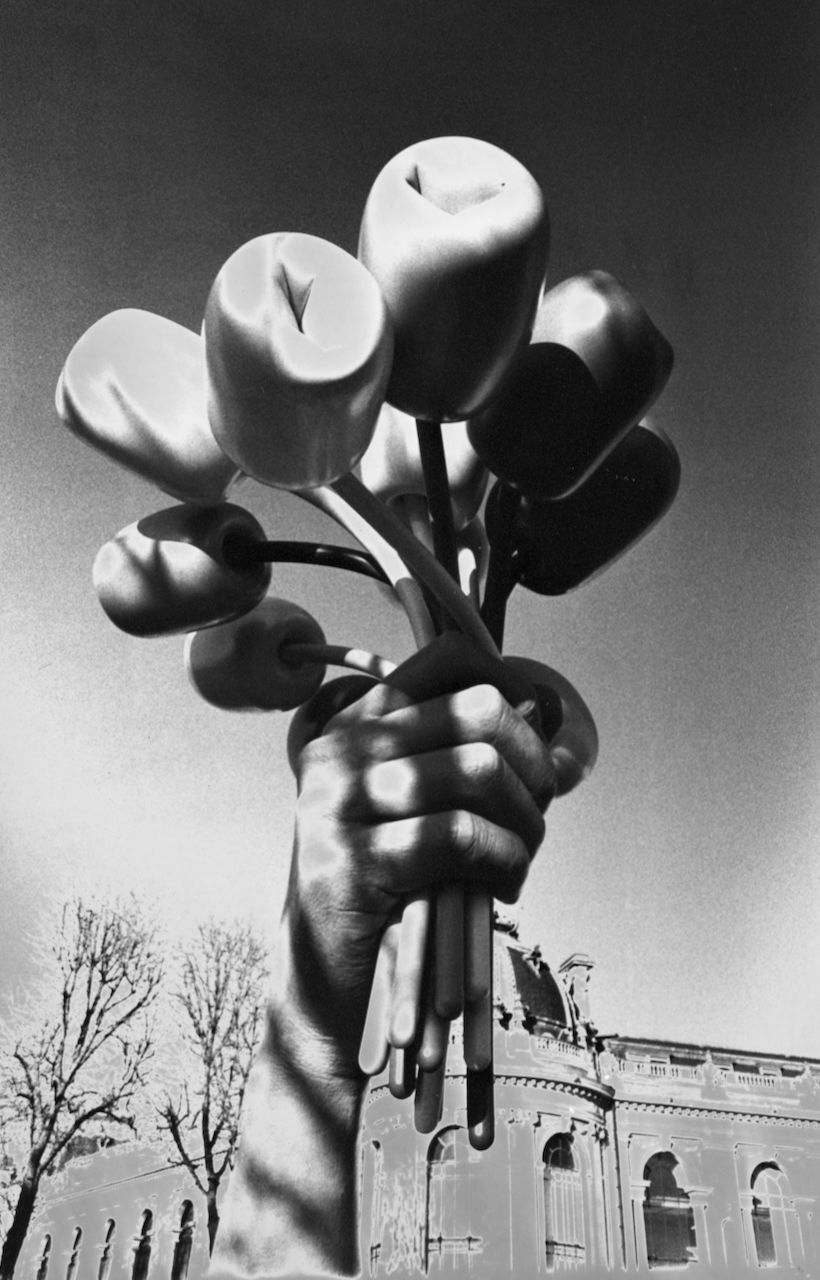

Not every print succeeded. Many ended up in the reject pile—too muddy, too chaotic, or simply uninteresting. But the successful ones revealed Paris in ways I hadn't anticipated while standing on those streets with my camera. Architectural lines gained glowing halos from the Mackie line effect. The familiar cityscape became simultaneously itself and its negative, existing in an ambiguous space between light and dark.

What emerges isn't Paris as tourists see it, but Paris reimagined through chemical intervention—a city of lights transformed by light itself. The process doesn't just depict the city's luminosity; it performs an operation on it, pushing photographic materials beyond their intended limits to reveal something unexpected.

Light Beyond Documentation

These Sabattier prints don't document Paris so much as interpret the experience of being there. They capture something about the city's relationship with light, but also something about the photographer's relationship with both—the way travel compresses experience, the way darkroom work extends it, the way experimental processes can uncover dimensions invisible to straight photography.

The technique that Man Ray adopted to “escape from banality” in the 1930s still serves that purpose today. Paris will always be the City of Lights. Through Sabattier—a process born from accidents and perfected through intention—these photographs take the city's luminous reputation and push it through one more transformation in the darkness of the darkroom.