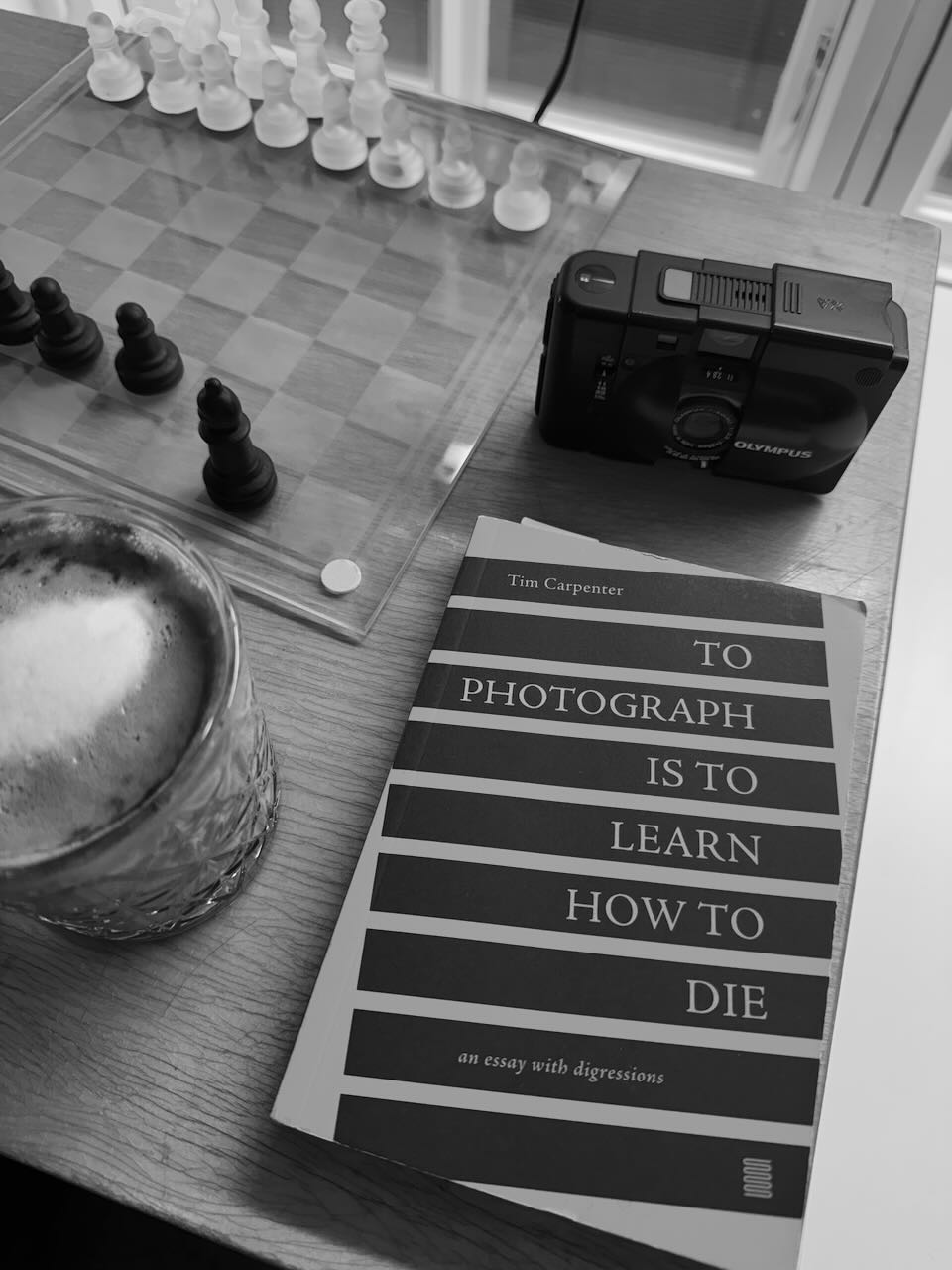

This post shares a personal and reflective essay I wrote earlier in the summer, inspired by Tim Carpenters To Photograph is to Learn How to Die. It explores photography as a way of engaging with time, mortality, and the fleeting nature of moments—especially through analogue and darkroom practice.

Please forgive my more academic musings here; I hope you’ll find something meaningful in this slower, deeper take on photography.

Finding Mortality Through the Lens: Reflections on Tim Carpenters To Photograph is to Learn How to Die

As I sit in my darkroom, watching a lith print slowly come to life in the chemical bath, I often find myself thinking about time. How photography freezes it. How the darkroom process stretches it. How each image captures a moment that's already gone.

And it’s entirely different from our companion’s experience of the same journey.

This, in many ways, is the territory Tim Carpenter explores in his beautiful book To Photograph is to Learn How to Die (The Ice Plant, 2021). Through a series of thoughtful essays, Carpenter doesn’t treat photography as a technical skill or just a way to document things. He sees it as a practice of attention, acceptance, and, ultimately, mortality.

The Weight of Mortality in Every Frame

Carpenter's main idea is clear: “Unlike any other aesthetic object, the photograph is a thing that embodies transience: it is an action made of time… that results in a thing that endures in time.”

A photograph, he argues, isn’t just a record of the past; it’s a way of grappling with something fundamental: the desire to hold onto things that can’t be held. As someone who works with film photography and spends hours manifesting an image to slowly appear, I feel this every day. There’s a bittersweetness in knowing that, even as we capture something, it’s already slipping away.

Carpenter reminds us that photography isn’t just about seeing; it’s about becoming aware of how we see: “an intentional way of continually discovering and rediscovering integrations of self and not-self.” Each image, he suggests, is a momentary reconciliation between the inner world and the outer one—a brief truce between memory and reality.

The Meditative Quality of Film and Analogue Work

For those of us who still work with analogue processes—taking the time to set up a view camera, hand-developing negatives, and making prints in the darkroom—Carpenter’s focus on slowness feels especially relevant.

He writes, “Technical choices must be made with great care for your pictures, but even more importantly with the utmost respect for your separate self and your intelligence and the contents of your heart.” This is something I can definitely relate to. Every choice—film stock, developer, paper—becomes a meditation on what I value, what I notice, and what I mourn.

Carpenter also points out that our tools aren’t neutral: “Choices of aspect ratio or lens coverage or film type are not just things that impact how your prints look… they are the very structure of your mind when it meets the world with a camera.”

When I’m in the darkroom, under the soft red light of the safelight, I’m reminded how true this is. Every small decision is a way of shaping attention, of choosing what kind of world I’m ready to see—and to lose.

Between Documentation and Invention

One of the things Carpenter focuses on is the idea that photography isn’t just about capturing a moment, but about creating new relationships. “While we can’t arrange the world with a camera,” he writes, “we have the ability to create significant associations between the things of the world and time in the photograph.”

This idea—that photography is an act of creation and decreation, rather than just documentation—resonates deeply with my own experience of alternative processes like lith printing, mordançage, and sabattier. Manipulating the chemistry isn’t about distorting the subject; it’s about honouring the inherent subjectivity of seeing. The image emerges as a collaboration between intention, chemistry, and chance.

As Carpenter puts it: “The photographic enterprise of experimenting with and exploiting all these variables… is really just a specialized or concentrated version of the way in which all people know the world in moment-to-moment experience.”

Photography, in this sense, becomes a way of thinking—not illustrating preconceived ideas, but engaging in real-time, embodied thinking. It’s a “real in-the-moment thinking… when the impetus to the picture and the picture itself are one and the same.”

A Philosophical Landscape

It’s easy to draw comparisons between Carpenter’s ideas and those of earlier thinkers on photography—Sontag, Barthes, Flusser—but his tone and priorities are distinct.

Sontag famously warned that “all photographs are memento mori,” viewing them as a kind of predatory act. Carpenter agrees that photography is closely tied to death, but he sees this not as a flaw but a gift: an opportunity to confront mortality with care, and even love.

Where Flusser looked at how cameras “program” our seeing, Carpenter focuses less on the technology and more on photography as a human practice. For him, it’s about how we reconcile ourselves with the transience of experience.

Where Barthes found a “punctum”—a sharp, painful wound in a photograph—Carpenter offers something gentler: the idea that by looking attentively, we can reconcile the real with the imagined.

As Carpenter writes, “Preserving the self has meant, in my case, making photographs (lots of them) in a conscious attempt to reconcile the conflict between what is and what is not.”

Conclusion: Looking for America

To Photograph is to Learn How to Die isn’t a traditional technical manual. It’s more of a meditation on living with intention in a world we can never fully grasp—much like Paul Simon’s travelers who search for something they can never fully define: a place, a feeling, a sense of belonging that’s always just out of reach. The song ends, not with arrival, but with yearning.

For Carpenter, photography isn’t about preserving a fixed world. It’s about learning how to engage with a world in motion, to understand that fleetingness is the only constant.

Living in Helsinki for the better part of a decade, far from my home in the north of England, this feeling is especially poignant. I just returned from a visit to the UK, retracing old steps in familiar places, now reshaped by time and change as a harmonious balance to the way they shaped me. Just like in America, there’s a search for something—the places, the feelings, the fragments of home—that never quite match what you remember. Photography, in this way, becomes a continual reach for something fleeting, something just beyond our grasp: that moon rising over the open field.

For those of us still working with film, chemistry, and analogue processes—believing in the slow emergence of an image through light and silver—Carpenter’s reflections are deeply reassuring. He reminds us that photography isn’t about freezing moments in time. It’s about participating meaningfully in their passing.

In a world obsessed with instant capture and endless sharing, Carpenter offers a quieter, more profound vision: one where photography becomes a disciplined practice of love and attention, a mortal praise of all that must slip away.

We are all, perhaps, looking for America.

For Carpenter, Photography teaches us to look—and to understand that looking is enough.

Final Thoughts

Carpenter’s book and practice spoke to me personally, offering a perspective on how photography connects us to time and the fleeting nature of life. Especially as someone who works with analogue processes, I find his ideas a meaningful way to think about how we relate to moments that slip through our fingers.

Thanks for reading. I’d love to hear your thoughts or experiences if this resonated with you.